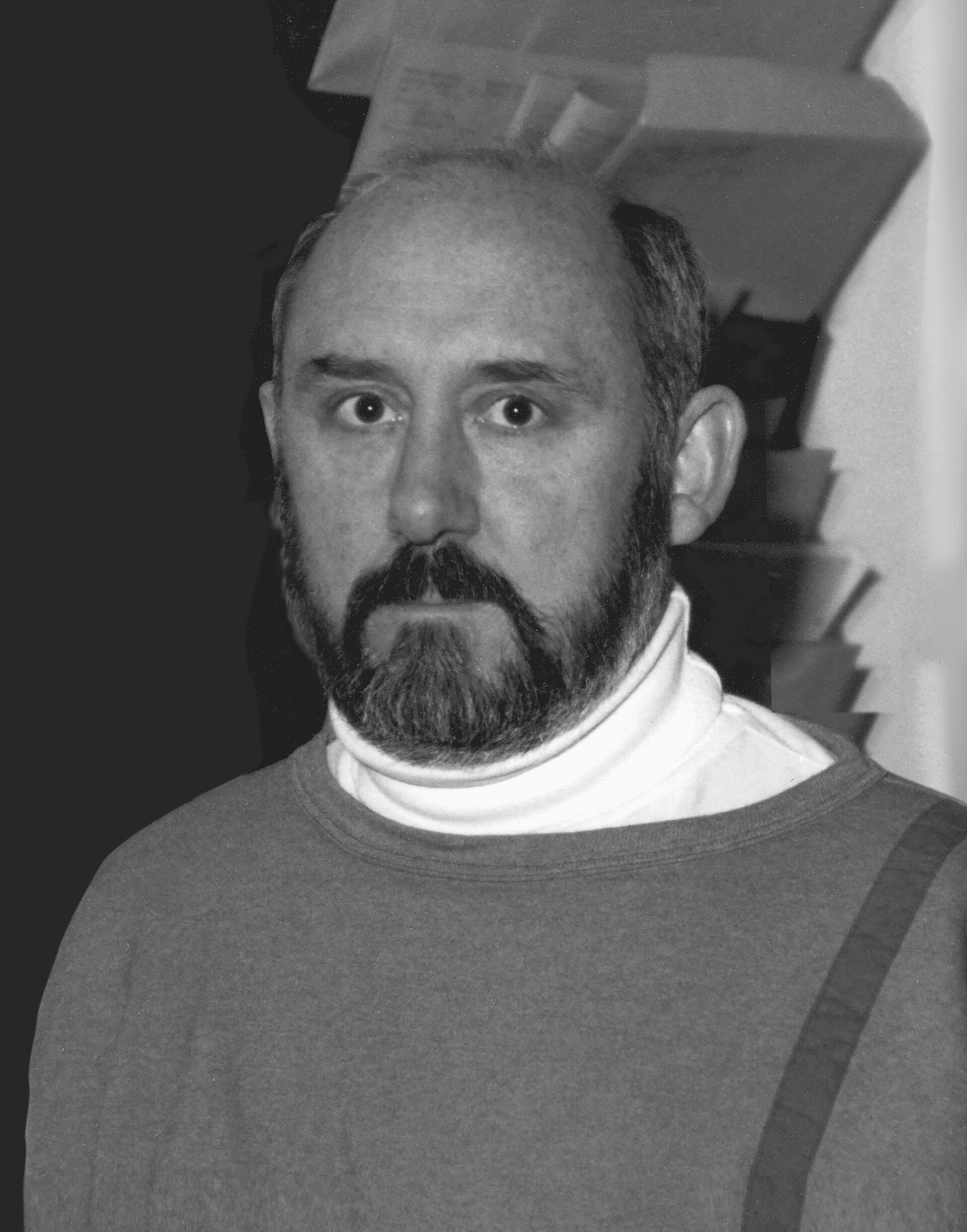

Profile: RN

Born: November 12, 1941

Location: Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Education:

Carey Grammar School, Melbourne (1953–1959)

Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT), Melbourne (1960–1963)

Studios:

Hanbury Advertising, Melbourne (1963–1965)

J. Walter Thompson Advertising, Melbourne (1965–1966)

Brigdens Ltd, Toronto (1966)

Wolf Inc, Buffalo NY (1966–1967)

Lawrence Wolf Canada Ltd (1967–1972)

Nash & Nash Ltd (1972–2014)

Achievements:

Art Directors Club of Toronto (ADCT), Board Director (1972-1973)

Association of Graphic Designers of Canada (GDC), Board Director, Toronto (1994–1996)

Association of Registered Graphic Designers (RGD), a Founder (1996)

Association of Registered Graphic Designers (RGD), Member (1996-present)

Association of Registered Graphic Designers (RGD), Board Director + VP (1996–1998)

Association of Registered Graphic Designers (RGD), Advisor to the Board (1999–2020)

Association of Registered Graphic Designers (RGD), Examination / Certification Board Director (2000–2020)

Association of Registered Graphic Designers (RGD), Membership Committee Member (2000–present)

Design Industry Advisory Committee (DIAC), Committee Member (2005–2015)

Ontario Government, Award for Dedicated Service to the Graphic Design Profession (2012)

Teaching:

George Brown College, Toronto (1982–1983)

Biography

Born in Australia during the Second World War, Rod Nash showed an early aptitude for visual thinking. From his school years, teachers recognized his artistic ability and encouraged him toward art at a time when instruction was still largely grounded in drawing and painting. A formative moment came in high school, when an art teacher introduced him to a colleague at the advertising agency J. Walter Thompson. This encounter offered Nash an early glimpse into professional creative practice and helped crystallize his ambition to pursue design as a career rather than a purely artistic pursuit.

In the early 1960s, as modernist design thinking was beginning to circulate internationally, Nash entered the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT), where those ideas were being actively introduced. Identified early for his potential, he was admitted directly into the second year of the four year Advertising Art program by department head Victor Greenhalgh, who viewed Nash and his classmate Barton Gole as part of a new generation of professionally trained designers. Under the guidance of Professor David Delgano, students were immersed in the principles of the International Typographic Style, learning to value clarity, structure, and reduction as tools for effective communication.

This education was reinforced through constant exposure to international design culture, particularly via publications such as the New York Art Directors Club periodical newsletter/magazines and also Graphis publications which offered rare insight into emerging global practices. The curriculum itself was rigorously practical, with long hours devoted to mastering foundational skills, hand lettering with ruling pens, sable brushes, and India ink, instilling both discipline and precision. By the time Nash completed his studies, he was equipped not only with technical fluency, but with an awareness that the most progressive work in the field was occurring beyond Australia’s borders, prompting him to aspire towards opportunities abroad when the time was right.

Nash’s first professional role at Hanbury Advertising in Melbourne involved working on one of Australia’s early corporate identity manuals for Liquid Air. The project resonated deeply with him, and upon hearing that the United States was the epicenter of this discipline, he resolved to work there. Facing difficult visa restrictions for Australians, he followed advice from colleagues who had just returned from Toronto. They described a vibrant design community and suggested that emigrating to Canada first would provide a viable pathway to the U.S.

Upon arriving in Toronto, Nash joined Brigdens, a major art studio and printing firm long associated with Eaton’s catalogues. There he learned the North American terminology and production practices that differed significantly from those in Australia. Brigdens employed a specialist dedicated solely to type markup, an invaluable source of knowledge for Nash as he adapted to new workflows and industry expectations.

From Toronto, Nash applied successfully for work authorization in the United States, joining Wolf Inc. One of his early accounts was Carborundum USA, whose modernist identity had been designed by Richard De Natale, already known to Nash through publications in Australia. Working directly with De Natale represented, for Nash, a defining milestone: tangible proof that his decision to cross the world had been worthwhile.

During this period, Nash contributed to the opening of Wolf’s Toronto office, producing work for clients on both sides of the border. Wolf’s longstanding relationship with Kodak became especially influential. Working on-site in Rochester, Nash was trained by some of the most knowledgeable photographic and film technicians in America, gaining a deep practical understanding of photography and slide presentation technology. Back in Canada, he applied this expertise in both design and photography for clients such as VW Canada, as well as in the creation of technically complex multi-screen dissolve slide shows, a highly specialized medium that gained prominence after Expo 67 and was mastered by relatively few studios in Canada.

In 1971, Wolf Canada hired Swiss designer Raphael Stolz, a former student of Armin Hofmann. Stolz brought with him the refined discipline and subtle ‘playfulness’ characteristic of Basel-trained designers, reinforcing Nash’s belief that modernist principles need not be rigid or doctrinaire to be effective. Nash’s work at Wolf reflected the synthesis of his early Australian training, Swiss influence, and North American practice, particularly in the identity programs and the packaging he developed for clients such as Strasenburgh Pharmaceutical and ESSO (Atlas).

In 1972, seeking full autonomy, Rod Nash co-founded Nash & Nash Limited with his wife Liz. The firm specialized in corporate identity management, producing and refining visual brands for a range of clients. Their particular strength was developing identity systems that were not only elegant but also practical and durable. Their manuals and guidelines were designed to be easily adopted by clients’ staff and suppliers across North America, ensuring consistency through inevitable corporate changes. This reputation for a highly workable approach to identity, backed by skilled research partners, sustained the practice through word-of-mouth referral.

Parallel to his design work, Nash became increasingly committed to strengthening the professional standing of graphic design in Canada. Noting that other professions benefited from government legislation, he worked throughout the 1990s to help establish a formal Act recognizing and regulating the graphic design profession in Ontario. The Registered Graphic Designers (RGD) Act, passed in 1996, remains one of the few such pieces of legislation in the world. In the process, Nash engaged directly with many of Canada’s most respected designers, several of whom appear on the Canada Modern website, gaining a deeper appreciation of the varied paths that led them into the field. This understanding later influenced the structure of the RGD examination process, acknowledging that designers arrive with diverse educational and professional foundations.

Rod Nash’s design philosophy aligns with a distinctly Canadian pragmatism seen in his contemporaries. He was, like Jim Donoahue, ‘never ideologically modernist… he saw modernism as just one of the tools at his disposal.’ This echoes Michael Pacey’s focus on client-specific solutions and Fritz Gottschalk’s desire to blend European discipline with a ‘freewheeling let’s-try-it attitude.’ Nash’s work represents this synthesis: a rigorous Modernist foundation, tempered by practical necessity and an openness to creative play, leaving a lasting mark on the professional and visual landscape of Canadian design.

Now retired, Nash reflects on a lifetime shaped by the evolution of modernist thinking and its adaptation across continents. He takes particular satisfaction in seeing that some identity work, his own and others too, has endured for decades. The enduring relevance of many modernist marks affirms, for Nash, that clarity, structure and reduction still have the power to remain both functional and timeless.